Most humans experience the world through the five senses of hearing, sight, smell, taste, and touch. Ironically, visual and auditory sensations often interact with each other. When we see a picture of a person shouting, we imagine a scream or a shout of anger; conversely, when we hear the sound of people laughing amidst the sound of many firecrackers, we imagine a fireworks display in a crowded square at Christmas. ‘The pictures are better on radio’ uses this sensory sharing to argue that a picture or scene seen on the radio can be more interesting to the audience than visual information without auditory information. However, it is not necessarily the case that presenting a play through auditory information alone is better than through visual information. In this article, I’ll give you a brief overview of Bonnie M. Miller’s argument and share my opinion on it.

Firstly, Bonnie M. Miller argues that it is more effective to convey visual information through an auditory medium, such as radio, where visual information is not present. This is due to the imagination of visual information through auditory stimuli: many of the situations that we have encountered in our lives are consciously or unconsciously remembered, and we envision them when we hear similar sounds. From an evolutionary standpoint, this mechanism is a survival instinct present not only in humans but also in animals. Before the development of civilization, humans and animals stored various information about their natural enemies in their senses to protect themselves when these senses were triggered. Imagination also offers the advantage of adapting to our personal preferences, allowing us to perceive scenes as more or less intense based on our individual inclinations.

However, there are a few blind spots in this theory.

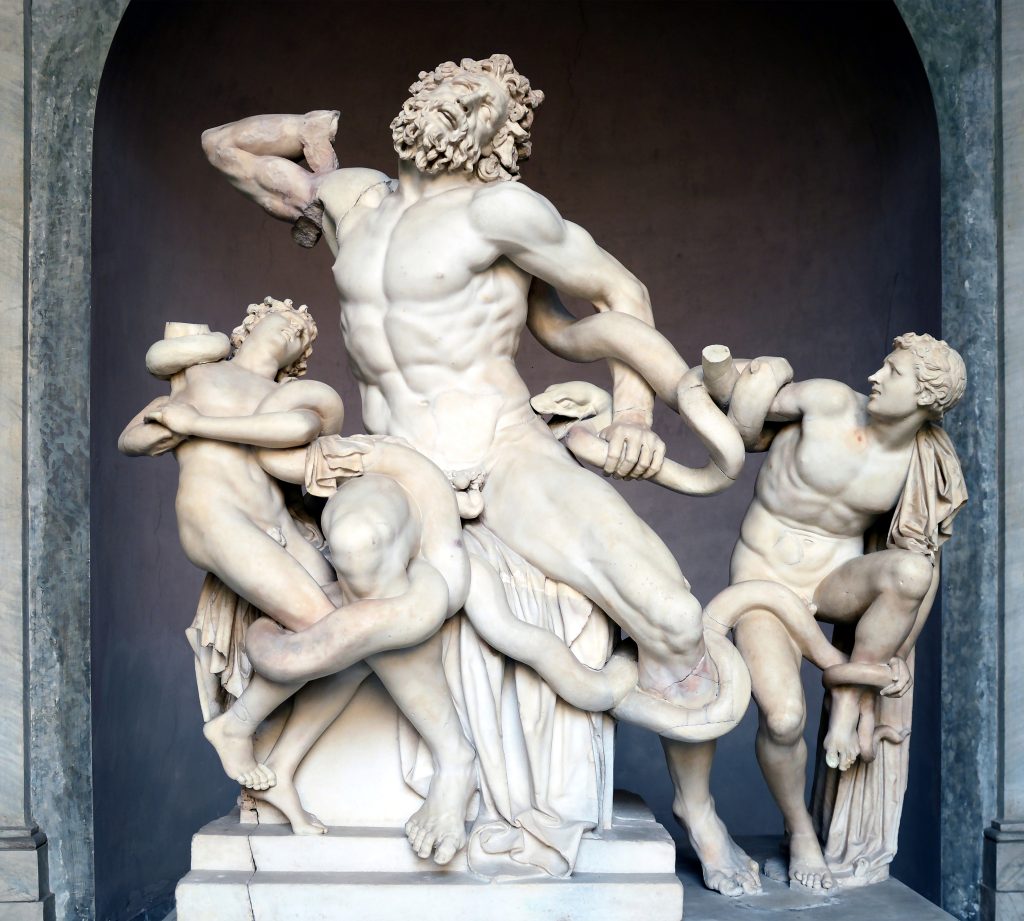

Firstly, imagination is constrained by an individual’s experiences. To illustrate, someone who has spent the first 20 years of their life in an orphanage will have a limited reservoir of visual information compared to someone with more varied experiences. This suggests that the effectiveness of this medium may vary depending on one’s background. Moreover, each person’s imagination is unique, so the visual imagery evoked by auditory stimuli may differ even if they receive the same auditory input. While this diversity may be an advantage of radio, it does not necessarily imply that radio surpasses photography with fixed visual elements. A photograph or a scene with predetermined visual information may limit the range of interpretations but also allows for diverse understandings within and among individuals. For instance, the statue of Laocoon in Greece, depicting Laocoon and his sons cursed by Poseidon, elicits varied interpretations, with some seeing it as a portrayal of helplessness and others as a depiction of agony. Thus, while auditory stimuli can stimulate the imagination, visual imagery can also inspire alternative interpretations, suggesting that radio’s advantage lies not in the superiority of imagination but in its unique mode of storytelling.

Certainly, radio’s ability to accentuate scenes or evoke emotions through appropriate sound effects can be advantageous in conveying auditory information. However, photography and silent films also encourage viewers to imagine the scenes and create accompanying sounds in their minds, albeit in a different manner. Therefore, while radio may excel in auditory storytelling, this does not imply that it is superior to photography.

Finally, photography offers the advantage of longevity. Unlike radio broadcasts, which are ephemeral and often consumed in the moment, photographs can be preserved and revisited over time, allowing for repeated interpretations. This enduring nature grants photography a unique appeal that radio broadcasts may lack.

In conclusion, while radio’s capacity to evoke visual imagery through auditory means can captivate audiences, photography offers its own charm by encouraging diverse interpretations. Rather than asserting the superiority of radio over photography, it is more accurate to acknowledge that each medium has its distinct appeal and strengths.