Bourriaud’s Relational Aesthetics has been interpreted, criticized, and expanded by various scholars from diverse perspectives, leading to a range of significant research developments. Claire Bishop, for instance, critiqued Bourriaud through the concept of antagonistic relational aesthetics, arguing that Bourriaud overly idealizes and harmonizes human relations, thereby neglecting conflict and tension within society. Bishop emphasized that genuine artistic practice must reveal underlying tensions and provoke critical discussion on social issues.

Grant Kester, from the viewpoint of dialogical art, proposed the concept of dialogical aesthetics, asserting that art could foster community transformation through egalitarian dialogue, thereby cultivating a spirit of collaboration and social responsibility. Lars Bang Larsen expanded the scope of relational aesthetics by suggesting the notion of socially engaged art, arguing that art should not merely create interpersonal relationships but seek real social change through sustained social action. Shannon Jackson, approaching relational aesthetics from the perspective of the public sphere, analyzed how relational practices can reconstruct public space through social participation, emphasizing that they must provide platforms for public expression and deliberation.

I. Claire Bishop’s Perspective

Through her discourse on Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics, Bishop critically examines and interprets Bourriaud’s theory. She particularly argues that relational artistic practices of the 1990s stemmed from a misreading of poststructuralism. According to Bishop, these practices misinterpreted the poststructuralist proposition that the interpretation of artworks should remain open to continual reevaluation, erroneously concluding that the artwork itself should exist in a state of perpetual flux. This misunderstanding, she warns, can make artworks difficult to identify and may transform exhibitions into market-friendly spaces for leisure and entertainment.

Bishop also contends that Bourriaud’s emphasis on the harmonious aspect of human interaction overlooks inherent contradictions and conflicts. From her viewpoint, Bourriaud’s framework presupposes an idealistic interaction devoid of conflict, whereas real-world human relationships are rife with tension, conflicting interests, and ideological differences. Bishop argues that if relational art avoids confronting these contradictions, it merely presents a superficial harmony. Thus, she asserts that art should reveal these tensions and spark critical discourse on social contradictions.

As an example, Bishop references Santiago Sierra’s performance in Havana, Cuba, in 1999, where he paid six unemployed young men $30 each to have a horizontal line tattooed across their backs. Titled 160 cm Tattooed Line on 4 People, this work provoked reconsiderations of social relations while also drawing antagonistic criticism. Sierra’s work, by commodifying human labor and satirizing the socio-political realities that produce such inequalities, partially diverges from Bourriaud’s framework.

According to Bishop, while Bourriaud’s relational aesthetics attempt to create utopian exchanges among individuals, they lack theoretical rigor in addressing capitalism’s inherent issues and the alienated reality it engenders. Bishop thus suggests that relational art must establish a critical dialogue between ideals and reality, reveal contradictions within human interactions, and stimulate imaginative visions for social reform.

II. Grant Kester’s Perspective

Kester, a leading figure in discussions on socially engaged art practices, developed relational aesthetics further through the lens of dialogical art. He posits that much of contemporary artistic practice aims to foster community dialogue, emphasizing conversation, mutual understanding through egalitarian communication, and community transformation. This marks a shift from conceptual art towards process- and interaction-focused dialogical art, underlining the importance of proper understanding and communication in artistic practices.

Kester discusses collective and collaborative practices, arguing that relational aesthetics must evolve beyond contingent interactions toward sustained dialogue and negotiation. He illustrates this through Suzanne Lacy’s project Between the Door and the Street (2013) in New York, where women wearing yellow scarves publicly engaged in discussions about women’s issues. Passersby could listen in, creating a living public discourse. This project stands out for successfully channeling casual conversation into public art while proposing its integration into policy.

Thus, while Bourriaud’s relational aesthetics emphasize the generation of social interactions, Kester’s dialogical aesthetics stress sustainability, negotiation, and ethical responsibility, providing a theoretical basis for deeper community engagement through art.

III. Lars Bang Larsen’s Perspective

Larsen introduced the concept of social practice art to complement and advance Bourriaud’s relational aesthetics. He argues that aesthetic and social understanding are inseparable: social relationships, as foundational units of analysis within social sciences, are formed through voluntary or involuntary interpersonal relations within and across groups.

Larsen critiques Bourriaud’s model for being ephemeral and superficial, noting that relationships formed within galleries cannot easily translate into sustainable societal effects. In contrast, social practice art involves direct interventions into social spaces, building enduring partnerships with communities and generating tangible social benefits.

A key example is Palle Nielsen’s Model for a Qualitative Society (1968), where he transformed Stockholm’s Moderna Museet into an adventure playground exclusively for children. This work challenged the elitist cultural norms of museums and fostered children’s freedom of expression through play. Larsen interprets Nielsen’s project as aiming for a utopian self-organizing society based on personal freedom and collaboration, aligning it with the “micro-utopias” Bourriaud emphasized.

Larsen’s work suggests that while relational aesthetics offer critical insights into contemporary art, there remains a need for expansion into sustained, purposeful, and organized social action.

IV. Shannon Jackson’s Perspective

Jackson reinterprets relational aesthetics from the perspective of the public sphere. She argues that relational art practices bridge the divide between art, the public sphere, and private life, aiming to reconstruct public spaces. Drawing on Jürgen Habermas’s theory of the public sphere, Jackson explains that the modern public sphere once functioned as a space for free communication outside state and market control but has since deteriorated under capitalist development.

Jackson emphasizes how media manipulation, corporate infiltration, and the privatization of public spaces have transformed public discourse into passive consumption of culture. In response, she views relational art as an effort to counter this decline by creating interactive situations that encourage egalitarian communication, thus offering a fleeting yet imaginative glimpse of a renewed public sphere.

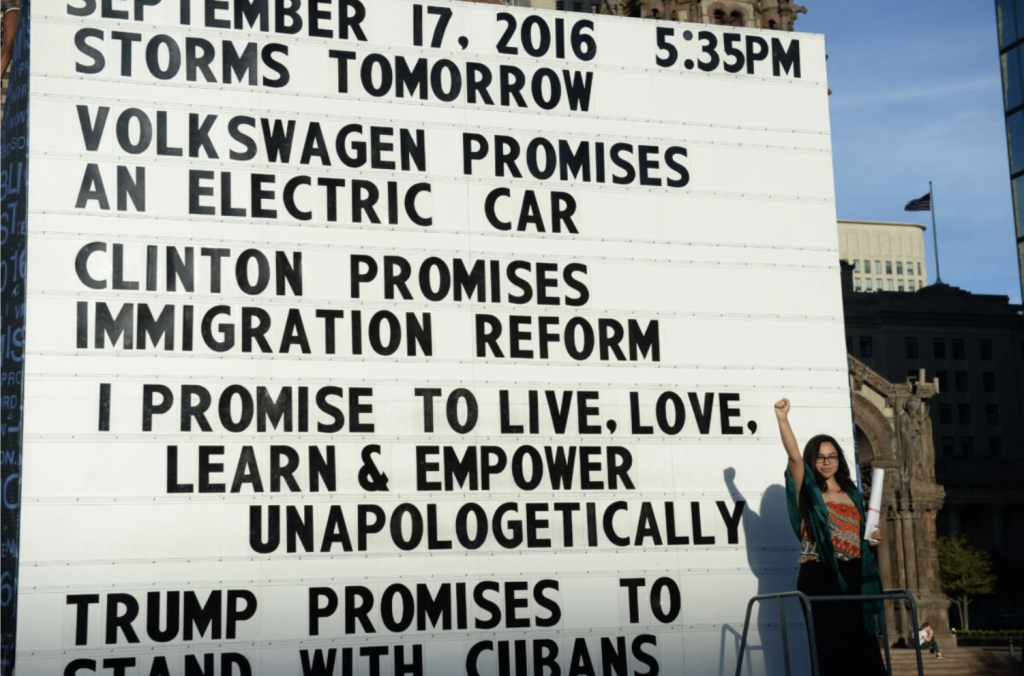

She cites Paul Ramirez Jonas’s Public Trust (2016) project, where participants made public pledges, thereby symbolically asserting their civic voice. This project transformed the museum into a site of citizen engagement and public reflection. Similarly, Tania Bruguera’s Museum of Immigration invited participants to share personal immigration experiences, promoting self-expression among marginalized groups and resisting cultural erasure. Her 10,148,54 Project at Tate Modern also used collective body heat to reveal hidden imagery, metaphorically illustrating communal existence despite political or ideological differences.

Jackson asserts that in the post-industrial era, the boundaries between art, labor, and production have blurred. Thus, artistic social engagement represents not just voluntary acts but a new form of labor. Her perspective expands the social implications of relational aesthetics, envisioning relational art as an effort to reconstruct public life and foster spaces for collective expression and negotiation.