In 1996, Bourriaud curated the group exhibition Traffic, featuring artists such as Philippe Parreno, Rirkrit Tiravanija, Carsten Höller, and Pierre Huyghe, who were engaged in relational-oriented practices. Relational Aesthetics consists of critical texts related to the artists featured in this exhibition, published by Bourriaud in art magazines. In Relational Aesthetics, he mentions that the core of contemporary artistic creation has shifted from the pursuit of aesthetic objects to the process of creating human relationships. That is, the relational art Bourriaud speaks of is not about presenting a completed object created by the artist, but about proposing the process of interaction formed incidentally and contingently as participants, producers, and interpreters engage in arbitrary spaces set up by the artist. Therefore, relational aesthetics is not a style or a school but is regarded as a new paradigm for interpreting contemporary art. Bourriaud’s relational aesthetics can be classified and analyzed into categories such as social interstice, micro-utopia, participation, and form of opening.

I. Social Interstice

In relational aesthetics, social interstice is one of the core concepts. He argues that art must create special social spaces where people can experience possibilities of social exchanges different from the inertia of daily life. These social interstices form a stark contrast with the formalized and materialized human relations of capitalist society. In this space, human exchanges are no longer bound by practical purposes or social norms, but are based on principles of equality, openness, and interaction, creating new modes of social connection. According to Bourriaud’s relational aesthetics, the core of contemporary art creation has fundamentally shifted, changing from the production of self-sufficient aesthetic objects to the generation of human relationships. His view reveals the internal link between modes of art production and forms of social organization as a new feature of contemporary art practice.

II. Micro-Utopia

The core of relational art creation lies in the transition from creating objects to creating relationships. This signifies the emergence of a new logic of artistic production. Relational artists no longer focus on creating unique and eternal aesthetic objects but emphasize forming situations and mediums for human interaction, thereby shaping social interactions. Thus, art no longer depicts grand utopias but forms concrete spaces. Bourriaud claims that the development of capitalism has caused the commodification and alienation of human relationships. Here, relational art has significance in opening up new possibilities for human exchanges through utilizing social interstices. Additionally, relational art recreates spaces of communication and dialogue, allowing people to temporarily escape the constraints of everyday life and to experience diverse social relationships, thereby forming micro-utopias. Through this, art gains a realistic function of directly forming social relationships. He argues that the interstices created by relational art provide spaces where people can temporarily escape from commodification and alienation. According to him, the space for human exchanges created within these interstices can form a special type of social relationship different from enforced exchanges. In this way, the interactions created by relational art allow people to temporarily escape the limitations of daily life and imagine different forms of social relations, thereby forming micro-utopias.

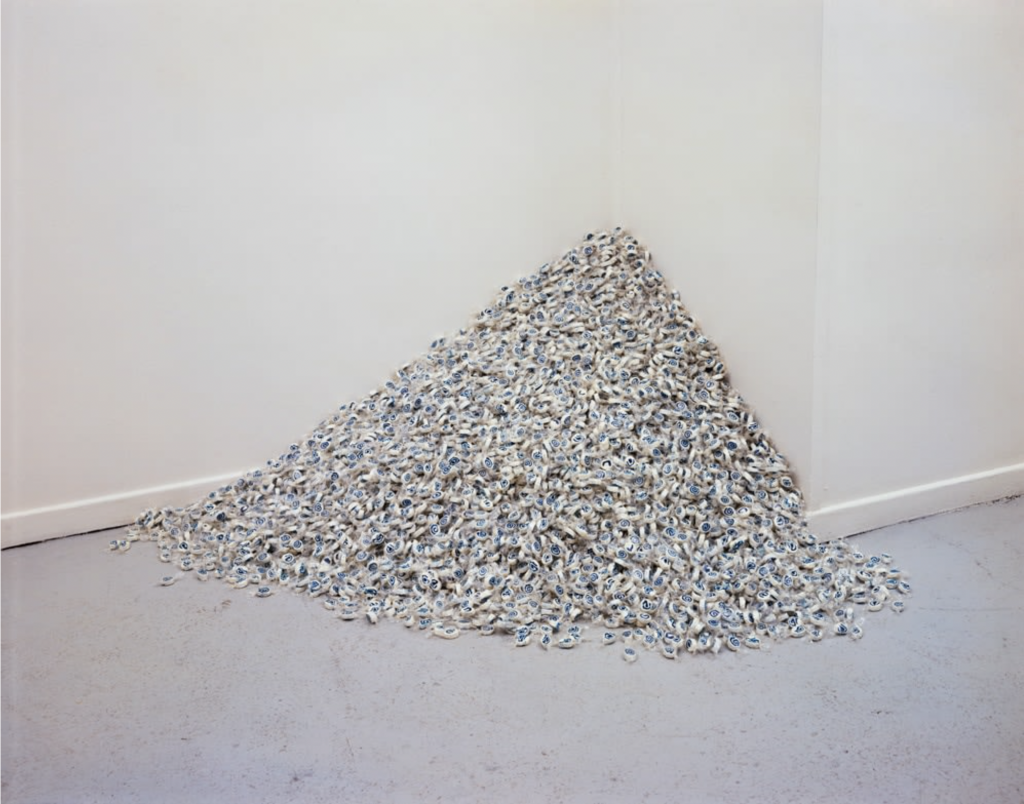

An example is Félix González-Torres’s Untitled: Rossmore (Lover Boys), where a pile of candies is used as a material for the artwork, serving as a representative case for understanding Bourriaud’s relational aesthetics. This installation art, where candies are piled in the corner of the exhibition space, invites the audience to freely take candies. González-Torres created this work in memory of his partner Ross Laycock, who passed away from AIDS. The candies symbolize their bodies, and by allowing the candies — everyday objects — to be taken by the audience, the gradual disappearance of the body and the longing for the lover are expressed. According to Bourriaud, artistic production now increasingly connects to the service industry and immateriality. Thus, those who produce artworks no longer actually “create” but instead “reconstruct.” In other words, the materiality of candies employed by González-Torres is linked to immateriality through the artist’s personal narrative, unfolding within the social interstice emphasized by Bourriaud, and this also forms micro-utopias.

However, voices continuously raise questions about the potential of the micro-utopias created by relational art. Some critics point out that the participatory interactions of relational art are limited by relatively closed spaces such as museums, raising doubts about how much relational art can actually intervene in and change everyday life.

III. Participation and Form of Opening

While explaining the concept of relational aesthetics, Bourriaud particularly emphasizes the openness of the forms of relational art. He explains that the core of relational art creation is no longer about making closed and self-sufficient aesthetic objects but about constructing open situations of interaction and inviting audiences into the process of meaning creation. In traditional art creation, artists followed a logic centered on the artist’s authority, emphasizing the artist’s unique creativity. Furthermore, art creation was seen as stemming from the artist’s innate and unique inspiration, and the artwork was emphasized as the externalization of such talent. In this context, the artist held the privilege of interpretation, and the audience played the role of passively appreciating and interpreting meanings predefined by the artist.

In contrast, relational art challenges the concept of the artist’s authority and emphasizes the open generation of meaning. Relational art is no longer a closed product of an artist’s personal expression but functions as an open framework of interaction that provides contexts and clues for audience participation. According to Bourriaud, the artist presents an overall framework, and the audience is invited to participate and play an active role in constructing the artwork. Thus, in relational art, meaning is completed only through audience interaction. In the context of relational art, the artwork is not a materialized expression of a pre-set meaning but acts as a starting point and medium for interaction.

The participatory, interactive nature of relational art means that the process of creating art is designed as a context of participation. The relational artist builds a platform for interaction and provides contextual elements to induce audience engagement but cannot completely control the process of meaning production. In other words, the artist’s role is to offer the potential for producing meaning through participation and creation, not to fixate meaning.

Thus, the interactive context of relational art includes various elements such as objects, symbols, spaces, and rules, and these harbor the potential for open meanings activated through audience participation. In this context, the audience is no longer a passive viewer but becomes a participant and collaborator in generating the artwork’s meaning. Particularly, participatory relational art moves beyond the structure of unilateral appreciation and leads audiences to intervene materially and symbolically in the artwork’s process. In this way, the audience’s diverse modes of participation and the corresponding interpretive contexts secure the possibility of pluralistic and open meanings even for a single work.

Bourriaud presents Rirkrit Tiravanija as a representative artist implementing this concept of relational aesthetics. His first relational aesthetics exhibition in 1990 in New York, Pad Thai, involved bringing cooking utensils into the gallery and serving Thai food to visitors, offering a participatory artwork. In this exhibition, Tiravanija went beyond merely connecting the artist and audience through hospitality, creating a situation that provokes reflection on simple materials, the environment, and establishes relationality. His relational aesthetic approach does not produce an aesthetic, technical outcome but invites the audience into the process of making the work itself.

Tiravanija’s work, instead of relying on material outcomes, offers situations where audiences can have their own experiences without implanted perceptions. According to Bourriaud, art is a way of learning how to live better in the world. It is a mode of living and an action model within existing reality, regardless of scale. Therefore, exhibitions, by triggering special fields of exchange, become special places where temporary gatherings occur, and relational aesthetics spaces can be understood as experimental places transforming traditional museums.

However, the open interaction of relational art also presents aspects that must be reconsidered. First, by transferring part of the responsibility of the artwork onto the audience, it can obscure the artist’s creative position. Also, not every audience member has the willingness or ability to participate, and situations must be applied differently depending on the emotional and cultural backgrounds of the participants. Above all, even if the audience does participate, the manner of their interaction may deviate from the artist’s intended framework.